The reciprocity of teaching and learning

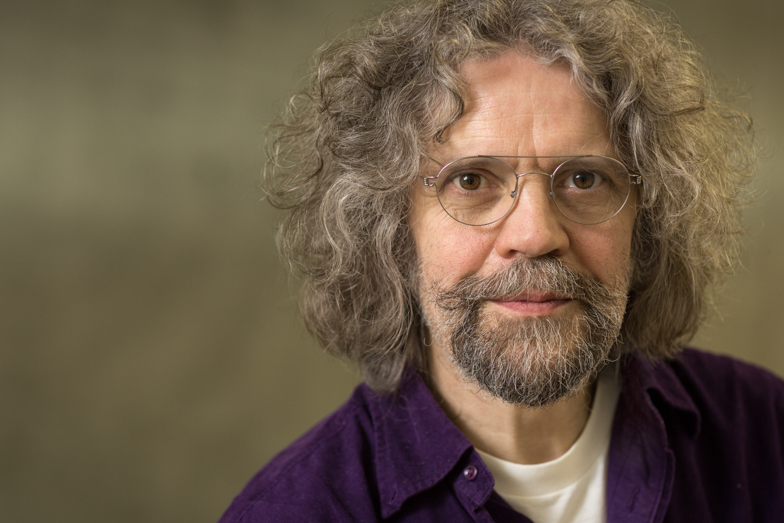

Franz Andres Morrissey

Dozent am Institut für englische Sprachen und Literaturen

Dr. Franz Andres Morrissey ist Dozent am Institut für englische Sprachen und Literaturen (85%), tätig in der LehrerInnen-Fortbildung im Bereich Creative Writing und Music in the Language Class Room, Esperto für Englisch im Kanton Tessin, aktiver Musiker, Autor mehrerer Märchenmusicals, humanistischer Aktivist, Familienvater mit drei erwachsenen Töchtern und einem Sohn, vierfacher Grossvater, hat während mehreren Jahren Verwandtenbetreuung geleistet.

Part of the furniture, that’s what I must be by now; at the end of the day someone comes with a cloth, dusts me down and puts me away for the night. And yet, every day of teaching, which is my primary calling at the English Department, is a reminder of how much I enjoy my work, engaging with lively minds, throwing questions into seemingly silent ponds, observing the ripples that develop, and more often than not, feeling that I can learn from what goes on as much as I hope my students do; teaching and learning are two-way processes.

One of the most gratifying experiences for me is to have students discuss their assignments with me, which they think are the best they can do, only to find that, with a little creative thinking, yes, they can do even better. In that sense I see my task not primarily as encouraging the high-flyers, but as promoting the skills that allow anyone willing to make necessary the effort to excel. That’s my idea of excellence, excelling one’s own expectations.

Coming back to the enjoyment I get out of my work, I find myself teaching three kinds of courses, each with its own great gratifications. The ones of the first kind are perhaps the most counterintuitive, the courses that I loathed when I was a student. Taking them on originally was a pedagogical challenge – can I make these more enjoyable than I experienced them – and I found over time as these most exciting moments in learning and research happened, the moment when things fall into place, that I had been wrong to hate these subjects. And I am often gratified that my students, while not all super-keen, seem to be comfortable enough with them and some are even enthusiastic.

The second type are those that focus on questions that deeply interest me, how humans interact with language, how they shape it while doing so and how creative they can be in the pursuit of their linguistic goals. It is fortunate that such questions are legitimate pursuits for research and that they allow me to sample other fields of enquiry than ‘pure’ linguistics, fields that include poetry, story-telling, drama, music, sociology, politics, law, pedagogy, etc.

The last category includes those courses, which I pursue because I passionately believe in their importance. As scholars and students we spend most of our lives and studies on analysis, on deconstructing, on unravelling, disentangling, unpacking or whatever fashionable synonyms we use for ‘taking apart’ in our quest for understanding. I am not suggesting these are not worthwhile goals, but I miss, and it seems my students seem to agree, the opportunities for ‘putting together’, for creating something. These courses, which I am not contractually required to run but enjoy far too much not to, are creative writing and translating texts from the page into a performance. Both of these seem somewhat un-academic and yet, the skills they practice are very useful indeed: a keen amateur cook appreciates the virtuosity of the master chef, the conscientious amateur poet has a different, possibly more insightful understanding of the creative process and the genius of the literary master, the student who tries to transfer a character’s words on a page, to embody them in a credible being on stage develops a feeling for nuances in what this character says.

But I am also fortunate enough to find enjoyable pursuits outside of my work. They provide a complete change, also from the committee work (less than I used to be involved in, but still enough to make me nurture the illusion that it sometimes makes a tiny difference), and from the bane of my job, the struggle with administrative IT work, which is meant to make life easier but I can’t really see whose. I hate the collecting of points like supermarket trophy points and the fiddle of keeping the system ticking over.

That’s why cooking and enjoying the company of friends and family out in the calming countryside at the bottom of the southwestern Frienisberg is such a crucial element in my life. And so are all the other extracurricular pursuits, teacher training activities, theatre projects, playing Blues and Folk, which all more often than not involve former students, and often also current ones, especially the time towards the small hours, when student parties deteriorate into lively sing-songs.

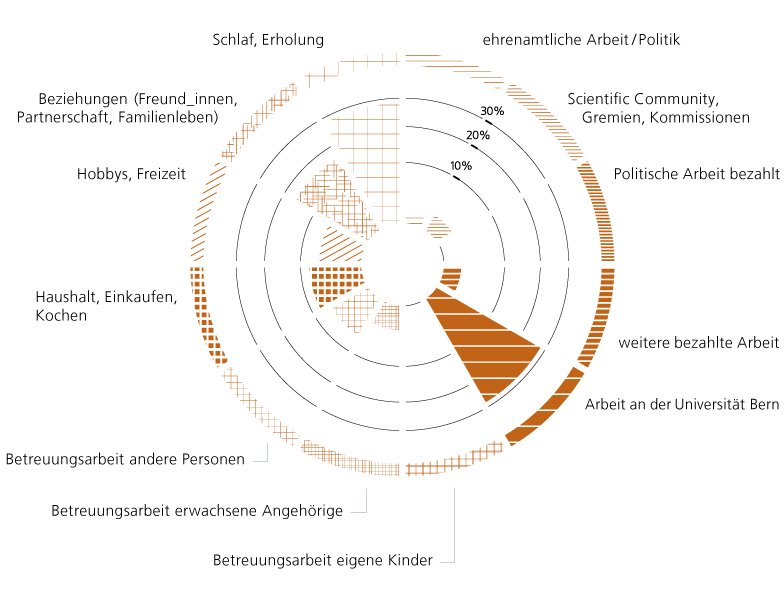

Wie verbringen Sie Ihre Zeit?

Prozentual Stunden pro Tätigkeit in einer durchschnittlichen Woche: